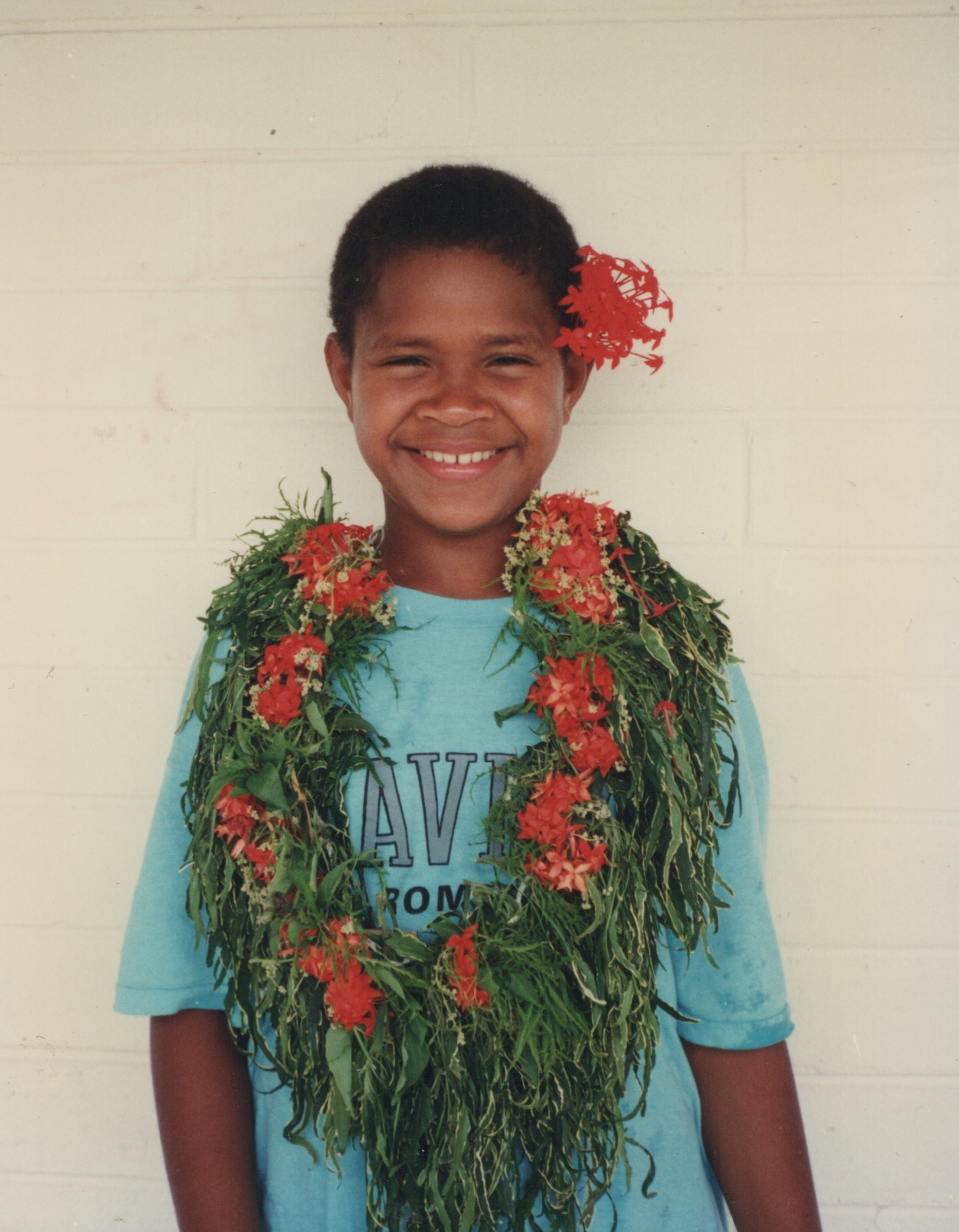

I am Found – Semaema’s Story

I was born in Fiji on 5 April 1986 and for the first four years of my life I knew nothing but unconditional love. I lived with my parents, Fulori and Sakiusa and maternal grandmother, Naula. They all doted upon me, I was the focus of their affection and delighted in the security and stability that such love brings. My parent’s marriage was not a happy one however, and when I was four years old they separated. A year later my mother left me in the care of my grandmother and moved to Australia to work. I missed her desperately but she called regularly and sent us bags of clothing, lollies, shoes, toys and money for savings. My grandmother cared for me with an intensity that had others accusing her of spoiling me. Perhaps she did, but I felt loved and safe. I adored her.

From time to time we would visit relatives who lived in Raiwaqa. I remember being dropped home after one such visit when I was seven years old. As I stood at the front door waving goodbye, my grandmother went to the backdoor, unlocked it and then walked through our house to unlock the front door from the inside. As she opened the door I ran inside, playful and full of energy. Within seconds, my grandmother was slumped to the ground in the doorway. I jumped on the sofa laughing, thinking that she was playing ‘Dead Bears’ the game where one of us pretended to be asleep. I called out to her but there was no reponse. I leant down beside her and as I looked at her face I realised that something was terribly wrong. It was pitch black outside but fuelled by shock and adrenaline, I ran as fast as my small legs could carry me through the darkened yard, until I reached our neighbours home. I knocked on their door and then….blank. I woke up to the sound of someone calling my name, ‘Semaema Semaema’. As I opened my eyes I saw people all around me, sitting on the floor.

My grandmother was dead.

I don’t remember crying. As the days went on, my home was filled with people whom I barely knew. They had come to bury my grandmother. In keeping with Fijian tradition, on the day of the funeral her coffin was brought to the house so that everyone could come and say their last goodbyes. When my turn came I remember the adults sitting by her coffin instructing me to say goodbye and kiss her. My mum, Fulori was on the phone from Australia, weeping and telling me to kiss grandma for her. I didn’t understand why my mother wasn’t there with me. I remember seeing my grandma Naula’s body, her Fijian hair combed nicely, her face pale without expression as if she was in a deep sleep. I leant forward and kissed her. I remember vividly how cold her cheeks were on my lips, like the feeling of a cold chicken that had just been taken out of the freezer.

Our family all packed into a van to travel to the gravesite. I sat by the window, trying to take notes in my mind of where we were going so that I could visit her again. When we returned to the house, relatives began sorting through our possessions. Who was I to say anything? I was just a child. As people began to leave, each taking with them with their handpicked selection of my grandmother’s belongings, a feeling of profound loneliness swept over me. I was seven years old and the two people I loved most in the world were now missing from my life. As the last family members got into their car I realised that I was being left behind. I ran as fast as I could, squished myself inside the already overloaded car and said ‘I’m coming with you’.

That’s how I found my next family.

My new family were part of my grandmother’s extended family. There were 12 of us in the home, a combination of aunties and uncles and cousins another grandmother, and me, the extra! They reluctantly accepted me into their home but it was very clear that I would not be treated as an equal member of the family. It was during this time in my life that the seeds of rejection began to take hold in my heart.

Sundays were my favourite days. The rest of the family usually slept in on Sunday morning, recovering from a late night of drinking kava and singing. I went to church on behalf of our family and I loved it. I was part of the choir. I loved to sing. Singing in the choir each week gave me an opportunity to express my emotions; to feel. Singing became my safe place, the place where I could be myself and the weekly rehearsals gave me a chance to escape the pain of my home life. When I was 10 years old, the adults of the family decided that they were no longer able to look after me and approached the Social Welfare Department about placing me with an orphanage. Within a matter of months I was told that there was an Australian couple who would like to adopt me and that I would be moving to Australia. I was curious about life in Australia but at the same time I remember wondering to myself ‘why does nobody here want me?’ My Fijian mother Fulori, had sent me a bag of clothes to take with me and told me to go to church, try hard at school and pray. She told me that she was also in Australia and that maybe we would be able to see each other one day.

I left Fiji full of excitement and nerves. I didn’t really understand what being adopted meant. I thought I was going for a little holiday, to stay in a mansion, with a big swimming pool and my own bedroom. It took a while for me to realize that I wasn’t going back to Fiji. I arrived into my Australian home on a Saturday, I went to church with my new family on Sunday (my adoptive father was the minister) and on Monday I started at school. My Australian adventure had begun. It did not take me too long to settle into my new life. I was a loving and affectionate child and made friends easily. I had been adopted in to a large family and was warmly embraced by the church community that played such a big role in my new family’s life. I enjoyed playing sport and socialising with my new friends but thoughts of my Fijian family, particularly my mother, were never far from my mind.

I can’t remember exactly when or how I found out about my birth story but when I did a lot of the disconnected pieces of my life started to make more sense. I discovered that the woman I had always considered to be my mother, was not actually my biological mother. She had raised me as her own daughter but had not legally adopted me. I was beginning to realise that there was a lot about my life that I didn’t know . When I was 13, my Australian parents received a phone call from Fiji. Fulori was dead. I was heartbroken. To make things even worse we found out that she had been living only two hours away from me. I don’t think anyone realised just how deeply I loved her and how desperately I wanted to see her. She was the first person who had loved me. She had established a foundation of unconditional love and identity in me that had helped me survive the darkest times in my childhood. My Australian father, John took me to her funeral. Fulori had left me her Bible and it contained an envelope with baby photos of me. As I looked through her Bible, read the passages she had underlined and the notes she had made, I felt close to her again.

My search for answers about my origin and identity was forced to take a backseat however, when I was diagnosed with Lupus.

Lupus is an autoimmune disease and in my case it manifested itself by attacking my organs. I was put on steroids that kept me stable for a while but in my late teens I had to go on chemotherapy, as the Lupus was no longer responding to the steroids. To protect my kidneys, I went on to cyclophosphamide. It’s a drug used to treat a lot of cancer patients. That was tough. My hair fell out, I lost a lot of weight and I was very isolated. My immune system was so low that I couldn’t be around most people in case they were sick or had an infection. It was hard not being able to be with my friends or go to church but I did a lot of singing and listening to music at home. I was very committed to not letting this disease conquer me or make me depressed. I was determined to be positive and to surround myself with positive people.

Despite these efforts however, and the support of my amazing family, I really struggled with the pressure of facing a life threatening illness whilst still processing my own sense of identity and value. I longed to know where I fit in the world. I craved contact with people of my own culture. My parents took me back to Fiji a few times and even found out the identity of my birth mum. Sadly she was not in a place where she was ready to acknowledge my existence. The circumstances of my conception were traumatic and as far as she was concerned I was a secret that she did not want revealed.

My adoptive parents were ministers and I had felt the pressure of being a good ‘church girl’ most of my life. So despite the challenges of my illness I lived the next few years of my life with a sense of reckless abandon and rebellion that involved some very foolish choices. Even though I had been on an aggressive regime of chemotherapy for over two years, at 21 I found myself pregnant, something doctors had told me was virtually impossible. It was a totally surreal experience. As shocked as I was to be pregnant, when I saw my baby on the ultrasound something deep and profound rose up on the inside of me. All my life I had longed for a connection with my own biological mother, with my ‘blood’ family and now I had it.

The child that was growing on the inside of me was my own ‘blood’ family.

Unfortunately there was little time for celebration. I was hospitalized as my illness took a turn for the worse. I was faced with the most difficult of circumstances imaginable. The combined pressure of the pregnancy and worsening disease on my already weakened body meant that I was faced with the unthinkable. The doctors were left with no choice but to terminate the life of my baby in order to save my life. I was absolutely devastated. There are no words that adequately describe the depth of shame and despair that descended on me at that point. My birth mother had abandoned me and now I was doing the same to my baby. Everything in me rebelled against the idea that I was exactly the same as my birth mother. I was distraught.

I spent the next three months in isolation, in hospital. It was without question the darkest time of my life. One night as I lay in bed I sensed the presence of ‘someone else’ in the room standing right beside me. I felt warmth and a sensation of being stroked or comforted. I turned to look at what it was and found myself staring at a dark winged creature with piercing black eyes. I was terrified. All I knew to do was call out the name of Jesus over and over. As I said His name the dark presence receded and eventually disappeared. All this time I had been so angry with God. I blamed him for allowing so many horrible things to happen to me. I blamed him for the burden of shame that I carried. He was the last person that I wanted to talk to yet as I looked back on all the mistakes and disappointments, the shame and rejection and the pain and suffering I also realized that God was the one constant presence in my life. Through it all He had never left me, rejected me or turned His back on me. In the darkest time of my life it was His name that I called out to and He answered me.

I picked up my Bible for the first time in a while and it came to life like never before. Words that had been just familiar, now became powerful and real. I realized that I had known God from a distance but as I read His word He became my personal savior and friend. As I poured over the Bible these verses from Isaiah 54: 4-5 almost leapt off the page.

“Fear not; you will no longer live in shame.

Don’t be afraid; there is no more disgrace for you.

You will no longer remember the shame of your youth”

As I read these words I felt a deep emotional healing go through my body. Even now when I read them they take my breath away ‘you will no longer live in shame’. What a powerful life giving promise. Even as my heart and soul were being healed my body continued to fight a battle against a disease that seemed to determined to destroy me. At the end of the three-month hospital stay the doctors informed me that they had exhausted all treatment options available. There was no cure and no other drug regimes left to try. They told me to go home, say goodbye to my friends and family and prepare to die. But I didn’t die!

After a period of time without any treatment at all, I began dialysis at Shellharbour Renal Centre and was put on the waiting list for a kidney transplant. Dialysis involved a trip to the hospital every second day for a five-hour process. The dialysis journey lasted for another four years; I still don’t know how I did it! In August 2013 I received a new kidney. I suffered with organ rejection issues for the first year but then my health stabilized. In 2016 I travelled to Fiji.

I was finally going to meet my birth mother.

My birth mother had agreed to meet me, and my Australian parents, in a hotel in Suva. The morning of our meeting I was a bundle of nerves. I was excited, anxious, and nauseous and as soon as I saw her I started crying. She was everything that I expected her to be, kind, softly spoken and very dignified. As we sat down and shared tea together she told me how sorry she was about what had happened. I thanked her for making the courageous decision to continue with the pregnancy and for giving me life. We said goodbye but made no promises about the future. Within a few months of returning from Fiji I began to get sick again. By June 2016 my donated kidney was no longer functioning as it should. In October I was in hospital, and back on dialysis. The transplant had failed. I needed a new kidney.

On 13 October 2016 I had reached the absolute end of myself. My health was failing and the years of rejection and feelings of unworthiness, overwhelmed my heart. As I listened to worship music I fell to my knees, sobbing from the very depths of soul. As I lay on the ground God gave me a vision of the day I was born. I saw Him standing next to my cot in the hospital, standing in the place where my mother had been, only now He was holding me. As I bowed my head in worship God handed the baby to me. I stood there holding the baby that was me, rocking and comforting the baby and speaking over her ‘you are loved, you are loved.’ I spoke to the baby girl, comforting her and enouraging her about the journey that was ahead and then I placed her back in God’s hands. She was not mine to carry any longer. Through tears I released the baby that was me, back to God.

My healing journey is ongoing. I am still waiting for a new kidney and my days are spent juggling the rigours of dialysis whilst still trying to enjoy the richness of life. I am still working through the deeper issues of my past, assisted by an incredible counsellor, and supported by an amazing community of friends and family. I live one day at a time, in gratitude and grace. My story is still being written and although it began with shame and rejection that is not how it will end. My story is a living story of grace, restoration and hope.